You're in the right place! Whether in nature, in the middle of the city, for families, in the countryside, historic or traditional: among Thuringia's TOP hosts, everyone will find exactly the right address.

Schiller's Holy of Holies

Schiller Museum and Residence

In Schiller's residence, located in the centre of Weimar on the former Esplanade, time seems to have stood still around 1800. It’s as if Friedrich Schiller has only just left and could walk in the door the next moment – at least that’s the impression. Bettina Werche, who as curator of Goethe’s art collection at the Klassik Stiftung Weimar is also responsible for Schiller's residence, knows, however, that “some rooms have been subsequently designed, i.e. staged. And not all the furniture is original by a long shot.”

The doctor of art history draws a comparison: “There was nowhere near as much family property handed down as in Goethe’s case, for example.” So the rooms had to be filled! Some of the original furniture was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp in 1942. Prisoners had to make replicas there, which in turn ended up in the residence. “The original furnishings were moved undetected to a bomb-proof depot,” says Werche. Fake or not fake? Even decades later, this question still remained. Schiller’s spinet, for example, was falsely presented as an “original” until 1998 – although not in his residence.

Everything in One Room: Sleeping and Writing

The Schiller desk made of dark fruitwood is unmistakably an original. Here in the study, the heart of the house, the master wrote his last dramas, “The Bride of Messina” and “William Tell”. The décor is also charming: an inkwell with a quill, a table clock and a celestial globe, and next to them, a simple spruce bed that is far too small. Schiller had it moved to the study. Despite his extremely poor health, he was obsessed with writing. The study therefore also became the place of his death on 9 May 1805.

The science is in agreement about these favoured, yet health-damaging wallpapers found throughout the entire house, whose materials consist of arsenic, copper and lead. That’s why these days the original wallpaper is nowhere to be found. But that doesn’t apply to the colourful and pattern-rich imitations that add to the warm charm of the house. This charm was also imbued by Mrs. Charlotte and the four children, whom the writer apparently took good care of (his specially invented, educational games suggest this). After Schiller’s death at the age of 45, the family continued to live in the building until it was acquired by the city in 1847 and a literary memorial to Schiller was established. “It’s the first German literature museum, if you will,” says Werche.

Ode to Joy: Past and Present

Its entrance can no longer be found on the esplanade, as it used to be, but in the auxiliary building, which was opened in 1988 and has been moved to the back. It is mainly used for special and temporary exhibitions. And functions as the start of the tour, which soon leads back to the actual residence. The XXL painting by Maximilian Stieler showing Schiller with his musician friend Andreas Streicher is a pleasant welcome. Afterwards, there are exhibits commemorating his stay in Bauerbach, where he found asylum after fleeing from Stuttgart. Afterwards, a room summarises Schiller’s life in Thuringia from 1787 onwards.

It was to be some time before he finally settled in Weimar, as we learn from charts and boards. In 1802 the time had come, and the decision was documented: “These days I have finally realised an old wish to own my own house. For I have now given up all thoughts of moving away from Weimar and intend to live and die here.” He was referring to the now yellowish house that visitors enter through a mini courtyard. In the ground floor rooms, statements from politicians, young people and artists about the European anthem, whose lyrics come from Schiller’s “Ode to Joy”, are presented on screens.

The Classical Duo: Schiller and Goethe

On the upper floors things become more personal, more intimate, more dazzling. Pictures and busts adorn the living room, dining room and Charlotte’s reconstructed room, including wallpapered corner cupboards. A copy of Anton Graff’s probably best-known portrait of Schiller greets visitors on the second floor, or more precisely: in the reception room. This is followed by the social room, in which Schiller somehow appears to be present in the form of a Dannecker bust. It was here where friends, acquaintances as well as prominent guests were welcomed for readings and discussions. A frequent guest: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, with whom Schiller was a close friend and with whom he is still mentioned in the same breath today, as the dream team of “Weimar Classicism”.

Meanwhile, it is precisely within these walls that it becomes clear how different the two were. On the one hand, there was Goethe, a statesman and industrious scientist who came from a good family and who never had to worry about money. And then there was Schiller, an often sickly, restless and homeless man who was enormously productive as a writer. This was also due to economic pressure. Again and again he was in need of patrons, gifts, and guarantors. He also took out a large loan to buy the house in 1802 for 4,200 taler. Which must have paid off, as he finally found the necessary peace and quiet for his work here.

The Experimental Workshop

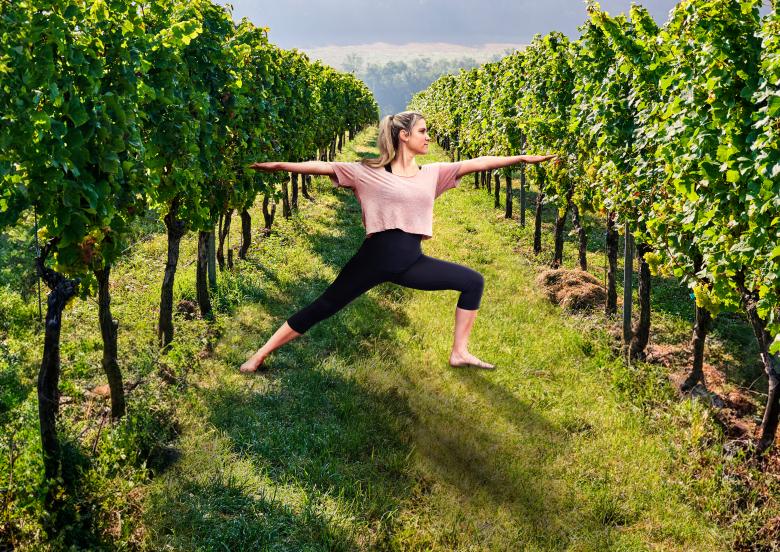

Header Picture: ©Florian Trykowski, Thüringer Tourismus GmbH

Accessibility

Did you like this story?

Visitors' information

Angebote

Booking

You might also be interested in ...